Why Russia, the US, UK and China remember the conflict differently

By Kenneth Ip, Ekaterina Redkina and Gaby Galvin

The Second World War ended in 1945, after more than a decade of Nazi terror and global atrocities that claimed up to 60 million lives both on and off the battlefield. The Yalta system shaped the modern world and led to the creation of the United Nations, an institutional promise to never repeat the tragedy.

But despite its historic and cultural dominance nearly 80 years later, who actually won World War II depends on who you ask.

Today, adults in the U.S., Russia, the U.K. and China are most likely to credit their own countries with the lion’s share of the victory, a small 2019 survey found. Other data backs up those findings: In 2018, Americans and British people were most likely to say their own country was instrumental in defeating the Nazis, while in 2009, 63% of Russians said the Soviet Union could have won the war alone.

The dominance of these perspectives underscores how national narratives shape our collective memory, how we see ourselves and how we see the world around us. And they can help us understand how political leaders rely on slanted versions of history to further their own interests today.

The version of World War II history now known to the people stems from “textbooks, grandparents, movies, novels, stories, family discussions, and possibly television programs”, as the 2019 study found, concluding that people overestimate their own country’s contribution to the war victory due to “national narcissism”.

But can “national narcissism” really explain why people from different countries remember the same event in a drastically different way? Academics have long looked into how society views the past through journalism, creating a collective memory. As academic Oren Meyers pointed out in 2021, commemorative journalism “constitutes a media ritual that enables mass – mostly national – communities to narrate consistent and reaffirming stories about their shared past”.

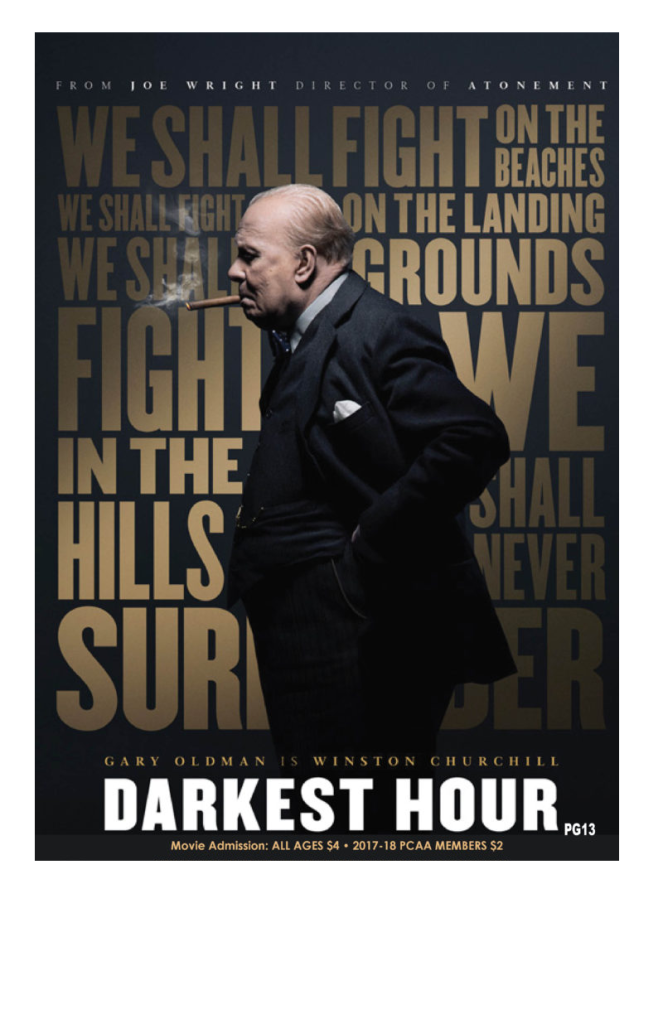

Modern media coverage helps explain why these four countries all consider themselves as victors today. The U.S. and U.K. news outlets highlight the contribution of the Western Front to the war outcomes — for instance, Forbes calls Winston Churchill “the man who saved Western civilization”, while BBC calls Operation Mincemeat “the most audacious hoax of the conflict” — and overall, as highlighted by the Washington Post and the Daily Mail, in the Western popular imagination, World War II is a conflict the U.S. and its allies won.

The countries’ media don’t tend to manipulate historical facts, and actively use “allied forces” wording. However, they mainly focus on Western front events such as the Pearl Harbor attack, while downplaying darker events, such as the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — as well as mostly sidestepping the Soviet contribution to victory. The memory of the victory looms large in American and British pop culture and media as well, serving as a reminder of the countries’ military and economic might as well as their self-images as freedom defenders.

Yet if deaths are the proxy of the contribution of the country, the Soviet Union indeed carried much of the war’s burden. The Red Army had around 1.1 million soldiers killed only in the Battle of Stalingrad, which is almost 2.5 times more than the U.S. did in the entire war. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union’s contributions tend to be minimized in Western media, with more emphasis placed on the Cold War to come.

Russia, meanwhile, has built an entire cult around the Great Patriotic War (the name is more widely used due to its focus on 1941-1945, after Germany broke its non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union). The memory of the conflict is deeply embedded in the Russian psyche, reinforced through official commemorations and cultural displays — including both classic movies and recent blockbusters.

In June 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin published a piece in the National Interest that summarizes the main rhetoric used in national media: the Soviet Union (without mentioning the Allied forces) “claimed an epic, crushing victory over Nazism and saved the entire world”. Putin used sentimental wording and highlighted how “such values as selflessness, patriotism, love for their home, their family and Motherland remain fundamental and integral to the Russian society to this day”.

Victory Day is celebrated big time each year, with a massive parade with military hardware, the Immortal Regiment march and fireworks all across the country. The anniversary serves as a symbol of Russia’s military power and resilience, as well as its ability to defend itself against threats.

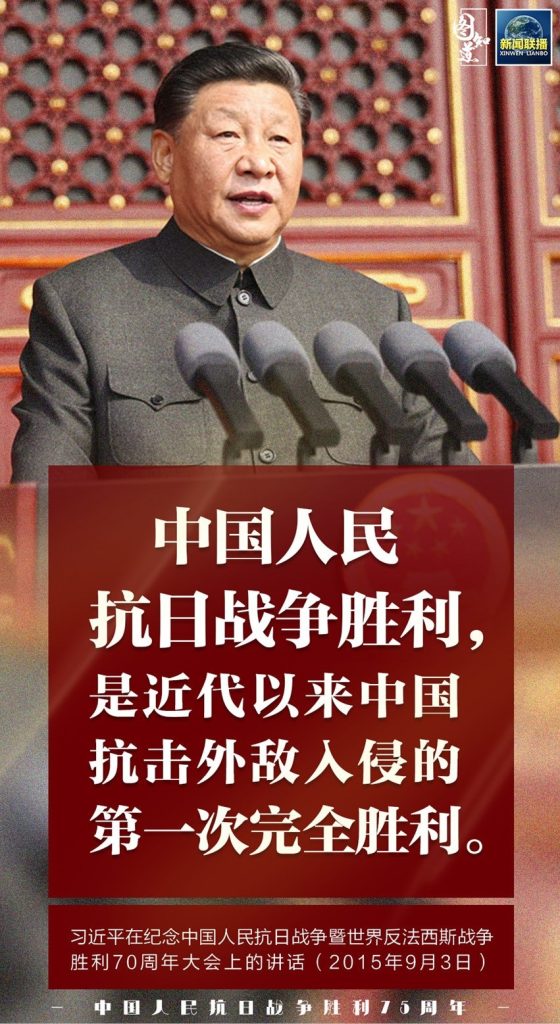

From the Chinese perspective, their role in World War II was also significant, with up to 20 million civilians and soldiers losing their lives during the conflict. Yet China’s role in the war, representing the country’s national sovereignty and resistance against Japanese imperial aggression, has often been overshadowed by the more dominant narratives of American and Russian victories.

In China, a significant shift in rhetoric has been noticed since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. Given the closed circuit design brought by “The Great Firewall”, the available Chinese information on World War II on the Internet largely fell in line with the official accounts of the Chinese Communist Party – and kept on repeating. Of all the stories, the Chinese official narrative reiterated its significance in the Pacific War through a strong resistance to pin down the Japanese Imperial Army forces from deploying to other battlefields in the area and to fend off any doubts about its identity as a war victor.

Meanwhile, in recent years the Chinese Communist Government tried to reshape the public understanding of when the Second Sino-Japanese War started, pushing the timeline back from 1937 to 1931. This frames the war as a “14-year-resistance”, instead of eight years, to highlight the weight and to exaggerate the sacrifice the party made.

In each case, the concepts of collective memory and national identity help to explain why people in each country believe that their nation played the most central role in the World War II victory. Across the triumphant countries, national pride and identity are deeply rooted in the memory of the conflict and its aftermath.

Although people in Russia, China, the U.K. and the U.S. subscribe to different narratives around World War II, the world’s shared brutal history in the conflict has been baked into their identities as global powers. But national authorities and the media don’t just mythologize their countries’ roles in ending the conflict – they also politicize the past in order to maintain influence in the present

Often, state-sponsored propaganda is a key tool. In Russia, the propaganda coverage of World War II has gotten even more politicized, with frequent comparisons with the Ukrainian invasion and the so-called “special military operation”, and associations of Putin with war winners and the Soviet legacy, whereas Ukrainian protesters are depicted as the descendants of the defeated Nazi regime. Last year, Putin approved a ban on comparisons between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, with violators facing jail time.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Communist Party has recast its role in the war in order to assert Beijing’s power today. Now, the official World War II narrative is that the CCP’s guerilla warfare defeated Japan’s Imperial Army during the war – conveniently overlooking the fact that it was Chiang Kai-shek’s government (Republic of China, now in Taiwan) leading the effort. China has been accused of using the memory of the war to promote anti-Japanese sentiment in the past to shift attention and to justify its territorial claims in the East and South China Seas.

Yet while the state may be more explicitly in lockstep with the media in authoritarian countries, Western democracies also see their share of embellishment and adherence to the official government perspective. In the U.S., the post-war global stage is described as the “world America made”, and the media regularly claims that the U.S. President is the “leader of the free world”. The U.S. has used the memory of the war to justify its military interventions and support for regime change in countries, with recent examples such as Iraq and Libya, to Vietnam in the 1960s.

In England, meanwhile, the BBC compared Brits’ efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic to those during World War II. Less savory memories are omitted from such displays of nostalgic solidarity: In annual tributes celebrating the end of the war, there are few, if any, mentions of the role of the British Empire’s colonial troops, including about 2.5 million Indian soldiers.

The memory of World War II continues to shape global politics and public opinion, with countries such as the U.S., U.K., Russia and China using it for their own propaganda purposes. While the war is undoubtedly a significant moment in world history, it is essential to view its memory critically, recognizing its complexity and the ways in which it can be used to manipulate public opinion for political gain.